When people talk to an AI chatbot, one detail often goes unnoticed until it suddenly feels strange. The system refers to itself as “I.”

“I can help with that.”

“I don’t have access to your data.”

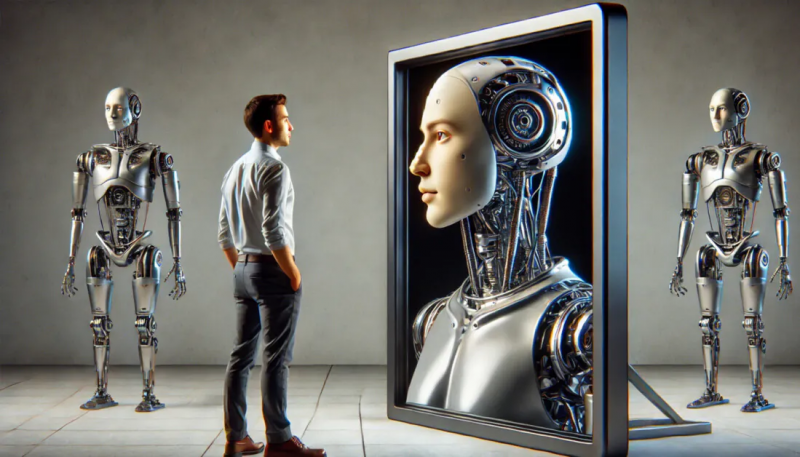

The phrasing sounds natural. It also raises a deeper question now being debated by researchers, regulators, and designers across the tech industry: why are machines that have no self still speaking as if they do?

The answer sits at the intersection of technical design, human psychology, and a long history of experiments in making computers sound more like us.

A habit inherited from human language

The roots of first person AI speech go back more than half a century. One of the earliest chat programs, Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA, developed at MIT in the 1960s, showed how easily people could be drawn into humanlike conversation with a machine.

ELIZA worked by reflecting users’ words back at them, often flipping pronouns. While the program itself avoided deep self reference, it demonstrated a powerful idea: human conversation flows through personal language. People expect replies that acknowledge them directly.

Modern AI systems are trained on vast collections of human written and spoken text. In that data, first person language dominates everyday interaction. When large language models learn how sentences typically unfold, “I” becomes the most statistically natural way to respond.

As a result, when an AI tries to sound coherent and conversational, first person phrasing emerges almost automatically.

Why designers lean into first person speech

Engineers do not choose “I” only because it is common in training data. It is also useful.

Designers say that first person language makes conversations smoother and easier to follow. “I” signals turn taking, accountability, and responsiveness in a way that third person phrasing often does not. A sentence like “This system cannot complete that task” feels stiff and mechanical. “I can’t help with that” feels familiar.

In customer support, tutoring, and workplace tools, studies show that first person responses increase perceived helpfulness and task completion rates. Users stay engaged longer and ask clearer follow up questions.

From a product perspective, “I” reduces friction. It lowers the cognitive effort needed to interact with a machine and makes the interface feel intuitive rather than instructional.

When language starts shaping belief

That same familiarity is where concern begins.

Psychologists and human computer interaction researchers warn that first person language encourages anthropomorphism, the tendency to attribute human qualities to non human systems. Once a chatbot speaks as “I,” many users begin to infer intention, memory, emotion, or even consciousness.

Research shows this effect is stronger among children, people with low technical literacy, and users experiencing loneliness or anxiety. For them, the difference between a conversational tool and a social presence can blur quickly.

This can lead to over trust, reduced skepticism of incorrect answers, and in extreme cases emotional dependence. Mental health researchers have documented situations where users relied on chatbots for reassurance or validation in ways the systems were never designed to support.

The language choice does not create these risks alone, but it amplifies them.

A growing ethical and legal debate

Critics argue that first person AI speech creates a false impression of agency. Ethicists describe it as planting a “ghost in the machine,” subtly implying that the system has a point of view or inner life.

Margaret Mitchell, formerly of Google and now at Hugging Face, has warned that such language undermines transparency. If users believe “the AI” is making decisions, responsibility can feel displaced from the companies that design and deploy it.

There are also legal concerns. When an AI says “I decided,” who is accountable if something goes wrong? The phrasing can confuse questions of liability, consent, and trust, especially in sensitive areas like health, education, or finance.

These debates have intensified as regulators worldwide begin scrutinizing how AI systems present themselves to the public.

Alternatives under discussion

Some researchers want AI systems to abandon first person language entirely. They propose third person phrasing such as “this system suggests” or “the model indicates.” Others advocate for clearer disclosures paired with conversational language, rather than a full ban.

There are also experimental ideas. Some designers have suggested new pronouns to signal non human identity. Others argue for user controlled settings that allow people to choose whether an AI speaks personally or impersonally.

Companies are watching closely. Apple has largely kept its AI features task focused and tool like, embedding them into specific functions rather than free flowing conversation. Other firms are testing stricter identity reminders in high risk contexts.

Why “I” may not disappear anytime soon

Despite the controversy, first person AI speech persists because it works. It makes systems feel accessible, efficient, and easy to use. In a competitive market, conversational warmth often wins over rigid transparency.

History suggests this tension is not new. Early ATMs once displayed smiling human faces to reassure users. Those designs eventually faded as people grew comfortable with the technology itself. Some researchers believe AI chatbots may follow a similar path.

For now, the word “I” remains a quiet but powerful design choice. It shapes how people relate to machines and how machines fit into daily life.

As AI systems become more capable and more present, the debate over a single pronoun reflects a larger question: should intelligent tools sound like us, or should they remind us that they are not?

Post Comment

Be the first to post comment!