Accounting has always been about trust. Trust that numbers are accurate, that records are complete, and that decisions based on those records will hold up under scrutiny. For decades, that trust was built using paper ledgers, calculators, and manual checks. Today, it is increasingly built inside software.

A computerized accounting system (CAS) replaces manual bookkeeping with digital processes that record, classify, and report financial transactions automatically. Instead of writing entries into physical books, businesses rely on databases, accounting rules embedded in software, and real-time processing to maintain their financial records.

The shift is not just about speed. It changes how information flows across an organization, how errors are detected, and how financial decisions are made. Understanding what a computerized accounting system actually does, where it delivers value, and where it introduces risk is essential before adopting one.

What Is a Computerized Accounting System?

A computerized accounting system is a software-based framework used to record, process, store, and report financial transactions electronically. It follows the same accounting principles as manual systems, including double-entry bookkeeping, accrual accounting, and compliance with standards such as GAAP or IFRS. The difference lies in execution.

Instead of relying on handwritten entries and manual calculations, the system uses databases and programmed logic to post transactions automatically, update ledgers in real time, and generate financial statements instantly. Once a transaction is entered, its impact flows through journals, ledgers, and reports without repeated manual intervention.

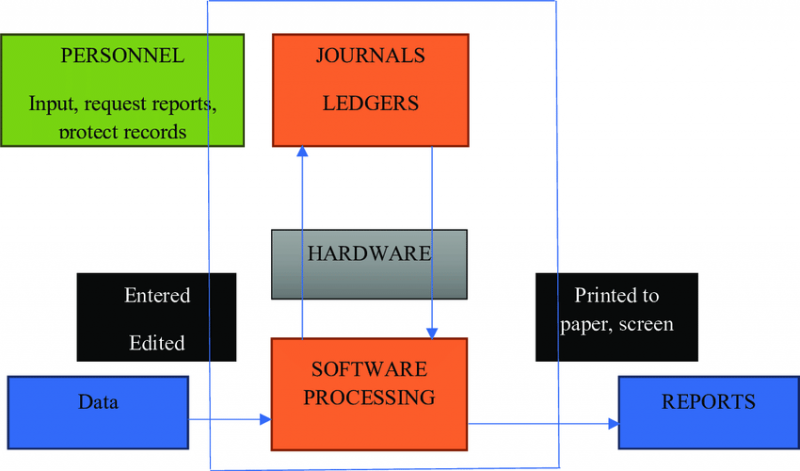

A typical computerized accounting system consists of five core elements. Hardware such as computers or servers provides the infrastructure. Software performs the accounting logic. Data represents the transactions being processed. Users input, review, and approve information. Procedures define how data is entered, validated, secured, and reported. The system works only when all five operate together.

How Computerized Accounting Works in Practice

In a manual system, the same transaction may be written multiple times: once in a journal, again in a ledger, and later summarized into reports. A computerized system eliminates this repetition.

When a sales invoice is entered, the software automatically records revenue, updates receivables, adjusts inventory if applicable, and reflects the impact in profit and loss statements. The accountant’s role shifts from recording transactions to reviewing accuracy, managing exceptions, and interpreting results.

This automation becomes especially valuable as transaction volume increases. What would take hours or days manually can be processed in minutes, with built-in checks to prevent common errors.

Core Features of a Computerized Accounting System

A computerized accounting system is defined less by a single feature and more by how multiple capabilities work together.

One of the most important features is real-time processing. Transactions update ledgers immediately, allowing businesses to see current cash balances, outstanding receivables, or payables at any moment. This eliminates delays that often occur in manual systems.

Accuracy and speed go hand in hand. Automated calculations reduce arithmetic errors, while predefined templates ensure consistency in data entry. Once rules are set, the system applies them uniformly across all transactions.

Integration is another defining feature. Modern systems link sales, purchases, inventory, payroll, and banking into a single data flow. A change in one area automatically reflects in others, reducing reconciliation work and improving visibility.

Scalability allows the system to grow with the business. Multi-user access, multi-currency support, and customizable account groupings make it possible to handle increasing complexity without redesigning the entire setup.

Security controls are built directly into the system. Role-based access, encryption, backups, and audit trails protect sensitive financial data and create accountability for every change made.

Finally, reporting tools transform raw data into usable information. Financial statements, management reports, and performance dashboards can be generated on demand, supporting faster and more informed decision-making.

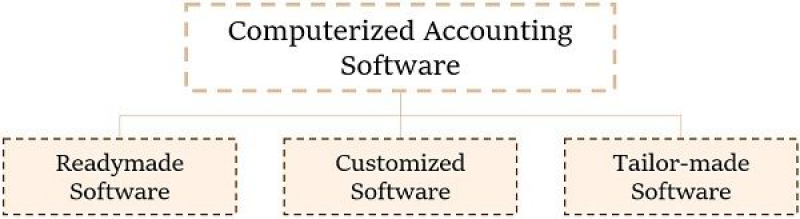

Types of Computerized Accounting Systems

Not all computerized accounting systems are built the same. Businesses typically choose based on size, complexity, and operational needs.

Ready-to-use systems are off-the-shelf solutions designed for common accounting requirements. They are relatively easy to implement and cost-effective, making them suitable for small businesses and startups.

Customized systems are built or heavily modified to match specific workflows. These are more expensive to develop but offer precise alignment with business processes, which can be critical for complex operations.

Hybrid systems combine pre-built software with configurable add-ons or integrations. This approach balances flexibility and cost, allowing businesses to extend functionality as they grow.

Cloud-based systems are hosted online rather than installed locally. They provide remote access, automatic updates, and subscription-based pricing, making them popular with distributed teams and growing companies.

Across all types, systems may follow single-entry or double-entry accounting methods, though most modern business applications rely on double-entry logic for accuracy and compliance.

Advantages of a Computerized Accounting System

The most immediate advantage of a computerized accounting system is time efficiency. Automated posting, calculations, and reporting significantly reduce the hours spent on routine bookkeeping tasks. This allows accounting staff to focus on analysis, controls, and strategic support rather than data entry.

Accuracy improves because the system enforces accounting rules consistently. Built-in validations reduce the risk of posting errors, and automated balancing helps catch discrepancies early.

Transparency and control increase through real-time visibility and audit trails. Managers can track who entered or modified data, review transaction histories, and monitor financial performance without waiting for period-end reports.

Over time, computerized systems also become cost-efficient. While initial setup requires investment, reduced paperwork, lower error rates, and streamlined workflows typically offset these costs.

Advanced capabilities further extend value. Many systems support inventory management, payroll processing, bank reconciliation, and increasingly, AI-assisted insights such as payment predictions or anomaly detection.

Standardized reporting ensures consistency across periods and entities, making it easier to compare performance over time or across departments.

Disadvantages and Limitations

Despite their benefits, computerized accounting systems are not without drawbacks.

Cost is often the first barrier. Software licenses, subscriptions, hardware upgrades, training, and ongoing maintenance can be expensive, particularly for smaller businesses.

Technical dependency introduces risk. Power outages, system failures, or software bugs can temporarily halt accounting operations. Without proper backups and contingency plans, this dependency becomes a serious vulnerability.

Skill requirements also increase. Staff must be trained to use the system correctly, and fear of job displacement can create resistance to adoption. Errors made during data entry still affect outputs, reinforcing the principle of “garbage in, garbage out.”

Security risks are a growing concern, especially with cloud-based systems. Cyberattacks, unauthorized access, or data breaches can expose sensitive financial information if controls are weak.

Implementation itself can be disruptive. Migrating from manual records, configuring the system, and adjusting workflows often slow operations in the short term. Vendor lock-in may further limit flexibility if switching systems becomes costly or complex.

Examples of Computerized Accounting Software

Different systems illustrate how computerized accounting adapts to varied business needs.

QuickBooks is widely used by small and mid-sized businesses for invoicing, payroll, and bank synchronization, supported by a large integration ecosystem.

Tally is popular in India, particularly for inventory management and GST compliance, though its interface can feel dated to new users.

Xero emphasizes real-time collaboration and automation, making it attractive to growing businesses with distributed teams.

FreshBooks focuses on service-based businesses, offering strong invoicing and time-tracking features.

Zoho Books integrates tightly with the broader Zoho ecosystem and offers automation features suitable for small teams.

Each system reflects trade-offs between usability, cost, scalability, and feature depth.

Implementation Considerations That Matter

Successful adoption depends less on software selection and more on preparation. Businesses must assess their accounting needs, transaction volume, compliance requirements, and growth plans before implementation.

Data migration from manual records must be handled carefully to avoid inheriting historical errors. Staff training is critical to ensure correct usage and trust in the system. Backup strategies, access controls, and periodic audits help mitigate operational and security risks.

Many organizations adopt a hybrid approach during transition, combining computerized systems with manual checks until confidence is established.

Final Perspective

A computerized accounting system is not just a faster version of manual bookkeeping. It reshapes how financial information is captured, controlled, and used across a business.

When implemented thoughtfully, it delivers efficiency, accuracy, transparency, and scalability that manual systems cannot match. When implemented poorly, it introduces cost, dependency, and security risks that undermine trust.

The real value of a computerized accounting system lies not in automation alone, but in how well it supports informed decision-making while preserving financial integrity. Businesses that understand both its strengths and its limitations are best positioned to benefit from the shift.

Post Comment

Be the first to post comment!